QUALITY Customers Can Rely On

Restaurants, Healthcare, Schools, Hotels, Industry, Homes

QUALITY Customers Can Rely On

Restaurants, Healthcare, Schools, Hotels, Industry, Homes

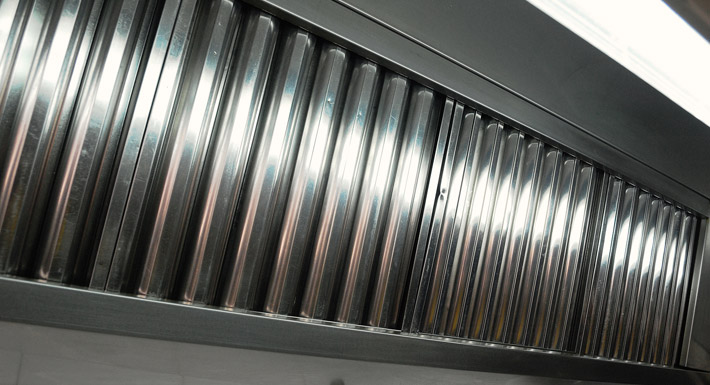

Air Maintenance Inc provides thorough and comprehensive commercial kitchen exhaust cleaning services. From the vent hood to the exhaust fan, our commercial cleaning experts pay great attention to detail cleaning your entire exhaust system.

Learn More

Keep your HVAC/r system performing at peak efficiency with regular cleaning service from the experts at Air Maintenance Inc. Our heating and cooling technicians provide efficient and effective HVAC/r system cleaning services to prevent future breakdown and ensure your system is performing at optimum energy efficiency.

Learn More

Air Maintenance Inc is dedicated to providing a safer, healthier environment to live, work and play. We are the only certified NADCA and IKECA Duct cleaning and WHEA construction contracting company in southeastern Wisconsin.

Learn More

Air Maintenance Inc provides expert ceiling cleaning services to deodorize and revitalize your ceiling. Cleaning your ceiling will improve light and provide a healthier, more inviting environment for a fraction of the cost compared to painting and replacement.

Learn More

Air Maintenance Inc has a wide scope of services to best suit the unique needs of our residential, industrial, commercial and healthcare clients. We are the only NADCA certified duct cleaning company and WHEA certified construction contractors qualified to provide air duct encapsulation and sealing services to healthcare facilities.

Learn MoreU.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission,

Office of Radiation and Indoor Air (6604J)

EPA Document # 402-K-93-007, April 1995

The following are excerpts from this booklet:

Information provided in this booklet is based on current scientific and technical understanding of the issues presented and is reflective of the jurisdictional boundaries established by the statutes governing the co-authoring agencies. Following the advice given will not necessarily provide complete protection in all situations or against all health hazards that may be caused by indoor air pollution.

All of us face a variety of risks to our health as we go about our day-to-day lives. Driving in cars, flying in planes, engaging in recreational activities, and being exposed to environmental pollutants all pose varying degrees of risk. Some risks are simply unavoidable. Some we choose to accept because to do otherwise would restrict our ability to lead our lives the way we want. And some are risks we might decide to avoid if we had the opportunity to make informed choices. Indoor air pollution is one risk that you can do something about.

In the last several years, a growing body of scientific evidence has indicated that the air within homes and other buildings can be more seriously polluted than the outdoor air in even the largest and most industrialized cities. Other research indicates that people spend approximately 90 percent of their time indoors. Thus, for many people, the risks to health may be greater due to exposure to air pollution indoors than outdoors.

In addition, people who may be exposed to indoor air pollutants for the longest periods of time are often those most susceptible to the effects of indoor air pollution. Such groups include the young, the elderly, and the chronically ill, especially those suffering from respiratory or cardiovascular disease.

While pollutant levels from individual sources may not pose a significant health risk by themselves, most homes have more than one source that contributes to indoor air pollution. There can be a serious risk from the cumulative effects of these sources. Fortunately, there are steps that most people can take both to reduce the risk from existing sources and to prevent new problems from occurring. This booklet was prepared by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) to help you decide whether to take actions that can reduce the level of indoor air pollution in your own home.

Because so many Americans spend a lot of time in offices with mechanical heating, cooling, and ventilation systems, there is also a short section on the causes of poor air quality in offices and what you can do if you suspect that your office may have a problem. A glossary and a list of organizations where you can get additional information are available in this document.

Indoor Air and Your Health

Health effects from indoor air pollutants may be experienced soon after exposure or, possibly, years later.

Immediate effects may show up after a single exposure or repeated exposures. These include irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, headaches, dizziness, and fatigue. Such immediate effects are usually short-term and treatable. Sometimes the treatment is simply eliminating the person's exposure to the source of the pollution, if it can be identified. Symptoms of some diseases, including asthma, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and humidifier fever, may also show up soon after exposure to some indoor air pollutants.

The likelihood of immediate reactions to indoor air pollutants depends on several factors. Age and preexisting medical conditions are two important influences. In other cases, whether a person reacts to a pollutant depends on individual sensitivity, which varies tremendously from person to person. Some people can become sensitized to biological pollutants after repeated exposures, and it appears that some people can become sensitized to chemical pollutants as well.

Certain immediate effects are similar to those from colds or other viral diseases, so it is often difficult to determine if the symptoms are a result of exposure to indoor air pollution. For this reason, it is important to pay attention to the time and place the symptoms occur. If the symptoms fade or go away when a person is away from the building and return when the person returns, an effort should be made to identify indoor air sources that may be possible causes. Some effects may be made worse by an inadequate supply of outdoor air or from the heating, cooling, or humidity conditions prevalent in the building.

Other health effects may show up either years after exposure has occurred or only after long or repeated periods of exposure. These effects, which include some respiratory diseases, heart disease, and cancer, can be severely debilitating or fatal. It is prudent to try to improve the indoor air quality in your building even if symptoms are not noticeable. More information on potential health effects from particular indoor air pollutants is provided in the section, "A Look at Source-Specific Controls."

While pollutants commonly found in indoor air are responsible for many harmful effects, there is considerable uncertainty about what concentrations or periods of exposure are necessary to produce specific health problems. People also react very differently to exposure to indoor air pollutants. Further research is needed to better understand which health effects occur after exposure to the average pollutant concentrations found in buildings and which occur from the higher concentrations that occur for short periods of time.

The health effects associated with some indoor air pollutants are summarized in the section "Reference Guide to Major Indoor Air Pollutants in the Home."

Some health effects can be useful indicators of an indoor air quality problem, especially if they appear after a person moves to a new residence, remodels or refurnishes a building, or treats a building with pesticides. If you think that you have symptoms that may be related to your building environment, discuss them with your doctor or your local health department to see if they could be caused by indoor air pollution. You may also want to consult a board-certified allergist or an occupational medicine specialist for answers to your questions.

Another way to judge whether your building has or could develop indoor air problems is to identify potential sources of indoor air pollution. Although the presence of such sources does not necessarily mean that you have an indoor air quality problem, being aware of the type and number of potential sources is an important step toward assessing the air quality in your building.

A third way to decide whether your building may have poor indoor air quality is to look at your lifestyle and activities. Human activities can be significant sources of indoor air pollution. Finally, look for signs of problems with the ventilation in your building. Signs that can indicate your building may not have enough ventilation include moisture condensation on windows or walls, smelly or stuffy air, dirty central heating and air cooling equipment, and areas where books, shoes, or other items become moldy (see www.epa.gov/mold6). To detect odors in your building, step outside for a few minutes, and then upon reentering your building, note whether odors are noticeable.

The federal government recommends that you measure the level of radon in your building. Without measurements there is no way to tell whether radon is present because it is a colorless, odorless, radioactive gas. Inexpensive devices are available for measuring radon. EPA provides guidance as to risks associated with different levels of exposure and when the public should consider corrective action. There are specific mitigation techniques that have proven effective in reducing levels of radon in the building. (See "Radon" for additional information about testing and controlling radon in buildings.)

For pollutants other than radon, measurements are most appropriate when there are either health symptoms or signs of poor ventilation and specific sources or pollutants have been identified as possible causes of indoor air quality problems. Testing for many pollutants can be expensive. Before monitoring your building for pollutants besides radon, consult your state or local health department or professionals who have experience in solving indoor air quality problems in non-industrial buildings.

The federal government recommends that buildings be weatherized in order to reduce the amount of energy needed for heating and cooling. While weatherization is underway, however, steps should also be taken to minimize pollution from sources inside the building. (See "Improving the Air Quality in Your Home" for recommended actions.) In addition, residents should be alert to the emergence of signs of inadequate ventilation, such as stuffy air, moisture condensation on cold surfaces, or mold and mildew growth (see www.epa.gov/mold6). Additional weatherization measures should not be undertaken until these problems have been corrected.

Weatherization generally does not cause indoor air problems by adding new pollutants to the air. (There are a few exceptions, such as caulking, that can sometimes emit pollutants.) However, measures such as installing storm windows, weather stripping, caulking, and blown-in wall insulation can reduce the amount of outdoor air infiltrating into a building. Consequently, after weatherization, concentrations of indoor air pollutants from sources inside the building can increase.

Usually the most effective way to improve indoor air quality is to eliminate individual sources of pollution or to reduce their emissions. Some sources, like those that contain asbestos, can be sealed or enclosed; others, like gas stoves, can be adjusted to decrease the amount of emissions. In many cases, source control is also a more cost-efficient approach to protecting indoor air quality than increasing ventilation because increasing ventilation can increase energy costs. Specific sources of indoor air pollution in your building are listed later in this section.

Another approach to lowering the concentrations of indoor air pollutants in your building is to increase the amount of outdoor air coming indoors. Most building heating and cooling systems, including forced air heating systems, do not mechanically bring fresh air into the house. Opening windows and doors, operating window or attic fans, when the weather permits, or running a window air conditioner with the vent control open increases the outdoor ventilation rate. Local bathroom or kitchen fans that exhaust outdoors remove contaminants directly from the room where the fan is located and also increase the outdoor air ventilation rate.

It is particularly important to take as many of these steps as possible while you are involved in short-term activities that can generate high levels of pollutants--for example, painting, paint stripping, heating with kerosene heaters, cooking, or engaging in maintenance and hobby activities such as welding, soldering, or sanding. You might also choose to do some of these activities outdoors, if you can and if weather permits.

Advanced designs of new buildings are starting to feature mechanical systems that bring outdoor air into the building. Some of these designs include energy-efficient heat recovery ventilators (also known as air-to-air heat exchangers). For more information about air-to-air heat exchangers, contact the U.S. Department of Energy's Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy's Office (EERE) at www.eere.energy.gov/7 ![]() 8. You may contact the EERE Information Center with questions on EERE's products, services, and 11 technology programs by calling 1-877-EERE-INF (1-877-337-3463).

8. You may contact the EERE Information Center with questions on EERE's products, services, and 11 technology programs by calling 1-877-EERE-INF (1-877-337-3463).

There are many types and sizes of air cleaners on the market, ranging from relatively inexpensive table-top models to sophisticated and expensive whole-house systems. Some air cleaners are highly effective at particle removal, while others, including most table-top models, are much less so. Air cleaners are generally not designed to remove gaseous pollutants.

The effectiveness of an air cleaner depends on how well it collects pollutants from indoor air (expressed as a percentage efficiency rate) and how much air it draws through the cleaning or filtering element (expressed in cubic feet per minute). A very efficient collector with a low air-circulation rate will not be effective, nor will a cleaner with a high air-circulation rate but a less efficient collector. The long-term performance of any air cleaner depends on maintaining it according to the manufacturer's directions.

Another important factor in determining the effectiveness of an air cleaner is the strength of the pollutant source. Table-top air cleaners, in particular, may not remove satisfactory amounts of pollutants from strong nearby sources. People with a sensitivity to particular sources may find that air cleaners are helpful only in conjunction with concerted efforts to remove the source.

Over the past few years, there has been some publicity suggesting that houseplants have been shown to reduce levels of some chemicals in laboratory experiments. There is currently no evidence, however, that a reasonable number of houseplants remove significant quantities of pollutants in homes and offices. Indoor houseplants should not be over-watered because overly damp soil may promote the growth of microorganisms which can affect allergic individuals.

At present, EPA does not recommend using air cleaners to reduce levels of radon and its decay products. The effectiveness of these devices is uncertain because they only partially remove the radon decay products and do not diminish the amount of radon entering the building. EPA plans to do additional research on whether air cleaners are, or could become, a reliable means of reducing the health risk from radon. EPA's booklet, Residential Air-Cleaning Devices9, provides further information on air-cleaning devices to reduce indoor air pollutants.

For most indoor air quality problems in the building, source control is the most effective solution. This section takes a source-by-source look at the most common indoor air pollutants, their potential health effects, and ways to reduce levels in the building. (For a summary of the points made in this section, see the section entitled "Reference Guide to Major Indoor Air Pollutants in the Home"). Ozone Generators That Are Sold As Air Cleaners10 (which is only available via this web site) was prepared by EPA to provide accurate information regarding the use of ozone-generating devices in indoor occupied spaces. This information is based on the most credible scientific evidence currently available.

"Should You Have the Air Ducts in Your Home Cleaned?"11 was prepared by EPA to assist consumers in answering this often confusing question. The document explains what air duct cleaning is, provides guidance to help consumers decide whether to have the service performed in their building, and provides helpful information for choosing a duct cleaner, determining if duct cleaning was done properly, and how to prevent contamination of air ducts.

Do You Suspect Your Office has an Indoor Air Problem?

Indoor air quality problems are not limited to homes. In fact, many office buildings37 have significant air pollution sources. Some of these buildings may be inadequately ventilated. For example, mechanical ventilation systems may not be designed or operated to provide adequate amounts of outdoor air. Finally, people generally have less control over the indoor environment in their offices than they do in their homes. As a result, there has been an increase in the incidence of reported health problems.

A number of well-identified illnesses, such as Legionnaires' disease, asthma, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and humidifier fever, have been directly traced to specific building problems. These are called building-related illnesses. Most of these diseases can be treated, nevertheless, some pose serious risks.

Sometimes, however, building occupants experience symptoms that do not fit the pattern of any particular illness and are difficult to trace to any specific source. This phenomenon has been labeled sick building syndrome. People may complain of one or more of the following symptoms: dry or burning mucous membranes in the nose, eyes, and throat; sneezing; stuffy or runny nose; fatigue or lethargy; headache; dizziness; nausea; irritability and forgetfulness. Poor lighting, noise, vibration, thermal discomfort, and psychological stress may also cause, or contribute to, these symptoms.

There is no single manner in which these health problems appear. In some cases, problems begin as workers enter their offices and diminish as workers leave; other times, symptoms continue until the illness is treated. Sometimes there are outbreaks of illness among many workers in a single building; in other cases, health symptoms show up only in individual workers.

In the opinion of some World Health Organization experts, up to 30 percent of new or remodeled commercial buildings may have unusually high rates of health and comfort complaints from occupants that may potentially be related to indoor air quality.

Three major reasons for poor indoor air quality in office buildings are the presence of indoor air pollution sources; poorly designed, maintained, or operated ventilation systems; and uses of the building that were unanticipated or poorly planned for when the building was designed or renovated.

As with homes, the most important factor influencing indoor air quality is the presence of pollutant sources. Commonly found office pollutants and their sources include environmental tobacco smoke; asbestos from insulating and fire-retardant building supplies; formaldehyde from pressed wood products; other organics from building materials, carpet, and other office furnishings, cleaning materials and activities, restroom air fresheners, paints, adhesives, copying machines, and photography and print shops; biological contaminants from dirty ventilation systems or water-damaged walls, ceilings, and carpets; and pesticides from pest management practices.

Mechanical ventilation systems in large buildings are designed and operated not only to heat and cool the air, but also to draw in and circulate outdoor air. If they are poorly designed, operated, or maintained, however, ventilation systems can contribute to indoor air problems in several ways.

For example, problems arise when, in an effort to save energy, ventilation systems are not used to bring in adequate amounts of outdoor air. Inadequate ventilation also occurs if the air supply and return vents within each room are blocked or placed in such a way that outdoor air does not actually reach the breathing zone of building occupants. Improperly located outdoor air intake vents can also bring in air contaminated with automobile and truck exhaust, boiler emissions, fumes from dumpsters, or air vented from restrooms. Finally, ventilation systems can be a source of in door pollution themselves by spreading biological contaminants that have multiplied in cooling towers, humidifiers, dehumidifiers, air conditioners, or the inside surfaces of ventilation duct work.

Use of the Building

Indoor air pollutants can be circulated from portions of the building used for specialized purposes, such as restaurants, print shops, and dry-cleaning stores, into offices in the same building. Carbon monoxide and other components of automobile exhaust can be drawn from underground parking garages through stairwells and elevator shafts into office spaces.

In addition, buildings originally designed for one purpose may end up being converted to use as office space. If not properly modified during building renovations, the room partitions and ventilation system can contribute to indoor air quality problems by restricting air recirculation or by providing an inadequate supply of outdoor air.

If you or others at your office are experiencing health or comfort problems that you suspect may be caused by indoor air pollution, you can do the following:

Call the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) for information on obtaining a health hazard evaluation of your office (800-35NIOSH), or contact the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, (202) 219-8151.

Where to Go for Additional Information on Indoor Air Quality

U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA)

Indoor Air Quality Information Clearinghouse (IAQ INFO)39

P.O. Box 37133

Washington, DC 20013-7133

(800) 438-4318; (703) 356-4020

(fax) 703-356-5386 or e-mail: iaqinfo@aol.com

Operates Monday to Friday from 9a.m. to 5p.m. Eastern Standard Time (EST). Distributes EPA publications, answers questions on the phone, and makes referrals to other nonprofit and governmental organizations.

How Do I Order a Copy of This Booklet?

This document is in the public domain. It may be reproduced in part or in whole by an individual or organization without permission. Single copies of this booklet are available from:

EPA's IAQ Information Clearinghouse (IAQINFO)

(800) 438-4318; (703) 356-4020

P.O. Box 37133,

Washington, DC, 20013-7133

iaqinfo@aol.com

or, you can order these publications directly via EPA's National Service Center for Environmental Publications (NSCEP) (www.epa.gov/ncepihom/).53 web site. Your publication requests can also be mailed, called or faxed directly to:

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

National Center for Environmental Publications (NSCEP)

P.O. Box 42419

Cincinnati, OH 42419

1-800-490-9198/(513) 489-8695 (fax)

Please use the EPA Document Number (# 402-K-93-007, April 1995), when ordering from NSCEP or from IAQ INFO.

National Air Duct Cleaners Association

Wisconsin Healthcare Engineering Association

International Kitchen Exhaust Cleaning Association

American Society for Healthcare Engineering

Wisconsin Restaurant Association

National Fire Protection Association

Milwaukee HVAC Cleaning Services Saves Energy The everyday use of Milwaukee heating and cooling sys...

Wisconsin Duct Cleaning and HEPA Filters for Improved Air Quality Air Maintenance Inc. is the premi...